2017 Sept – Feature article in Wired magazine on Resomation and the alkaline hydrolysis process

In the future, your body won’t be buried… you’ll dissolve

For centuries, humanity’s dead bodies have been either buried or cremated. Now, a growing movement is advocating for a cleaner, more sensitive alternative

By HAYLEY CAMPBELL

15 Aug 2017

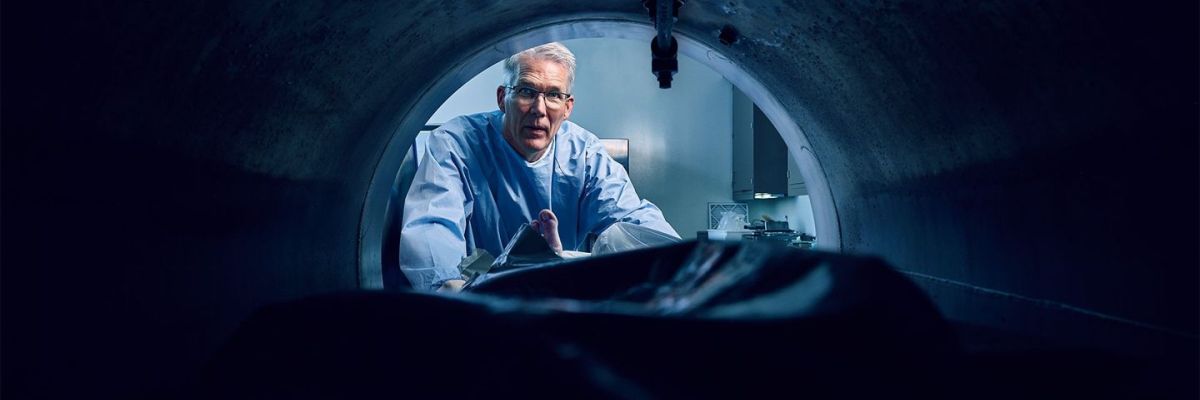

The Resomator stands monolithic in the corner of a room in the bowels of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). It’s as sterile as a hospital here, but every patient is already dead. This is the penultimate stage of their time under the care of Dean Fisher, director of the Donated Body Program at the David Geffen School of Medicine. Bodies are wheeled in under crisp sheets for disposal in Fisher’s alkaline hydrolysis machine, which turns them into liquid and pure white bone. Their bones will be pulverised and scattered off the coast by nearby Camp Pendleton, the Marine Corps Base, where they will float and then disperse, because pure calcium phosphate will not sink. From the coastguard’s helicopter it looks like drug lords flushing their stash.

The machine emits a low hum, like a lawnmower several gardens away. The cadavers awaiting grinding sit in blue plastic containers at the back of the room, identities anonymised by numbers and dog tags. The chalky bones are soft enough to destroy by hand: touch a femur and it falls apart.

Fisher has been running this model since March 2012 and he still can’t believe it, he’s gushing like it’s a car on a game show. It is one of only three in the United States, and not commercially legal in California. He’s removed the stainless- steel panels to reveal the inner workings, all the pipes and machinery that are neatly tucked away. Bodies go in through the same circular steel door that the British Ministry of Defence uses on its nuclear-class submarines. “It’s great, isn’t it?” he says, beaming behind his glasses. “Oh man, it’s just the best!” Fisher has the kind of personality you can’t help feeling is wasted on the dead.

“We’re sending our families into these intimidating industrial warehouses with

behemoth fire machines belching natural gas. It’s almost cruel.”

Caitlin Doughty, mortician

Photograph by Spencer Lowell

The machine is mid-cycle. Fisher, grey-haired and tall in light green scrubs, explains what’s happening inside the high-pressure chamber: potassium hydroxide is being mixed with water heated to 150°C. A biochemical reaction is taking place and the flesh is melting off the bones. Over the course of up to four hours, the strong alkaline base causes everything but the skeleton to break down to the original components that built it: sugar, salt, peptides and amino acids; DNA unzips into its nucleobases, cytosine, guanine, adenine, thymine. The body becomes fertiliser and soap, a sterile watery liquid that looks like weak tea. The liquid shoots through a pipe into a holding tank in the opposite corner of the room where it will cool down, be brought down to an acceptable pH for the water treatment plant, and be released down the drain.

Fisher says I can step outside if it all gets too much, but it’s not actually that terrible. The human body, liquefied, smells like steamed clams.

This, Fisher explains, is the future of death.